Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23 1915 after having signed a covenant of alliance with the powers of the Threefold Understanding and abandoning the deployment of the Triple Alliance. The front of contact between the two armies snapped in northeastern Italy along the alpine borders and the Karst region commencing war the following day. The Italian forces led by Chief of Staff General Army Luigi Cadorna launched a series of massive offensive fronts against the Austro-Hungarian defences in the Isonzo River region, held by General Svetozar Borojević’s Army Bojna. The conflict soon turned into a bloody war of trenches, similar to the one that was fought on the western front: the long series of battles on the Soonso lead the Italians to miserable territorial gains at the price of heavy losses between the troops. The Austro-Hungarian forces merely defended themselves by launching limited counterattacks, except for the massive offensive on the Asiago plateau in May-June 1916, blocked by the Italians.

The situation underwent a sharp change in October 1917, when a sudden offensive of the Austro-Germans in the area of Caporetto led to a breakthrough of Italian defences and a sudden collapse of the whole front: the Royal Army was forced to an extended retreat at the banks of the River Piave, leaving the enemy in Friuli and the northern Veneto in addition to hundreds of thousands of prisoners. Moving on to the guidance of General Armando Diaz and reinforced by Franco-British troops, Italian forces managed to consolidate a new front along the Piave, blocking the offensive of the Central Empires. After rejecting a further attempt by the Austro-Hungarians to force the Piave line in June 1918, the Allied forces went to the counter-offensive at the end of October 1918: during the so-called Vittorio Veneto battle the Austro-Hungarian troops were put in Broken, disintegrating during the retreat.

On November 3, the Austro-Hungarian Empire asked for and signed the armistice of Villa Giusti, which entered into force on November 4, marked the end of the hostilities.

The most challenging and cruel battles of the early years of the war occurred on the Isonzo front.

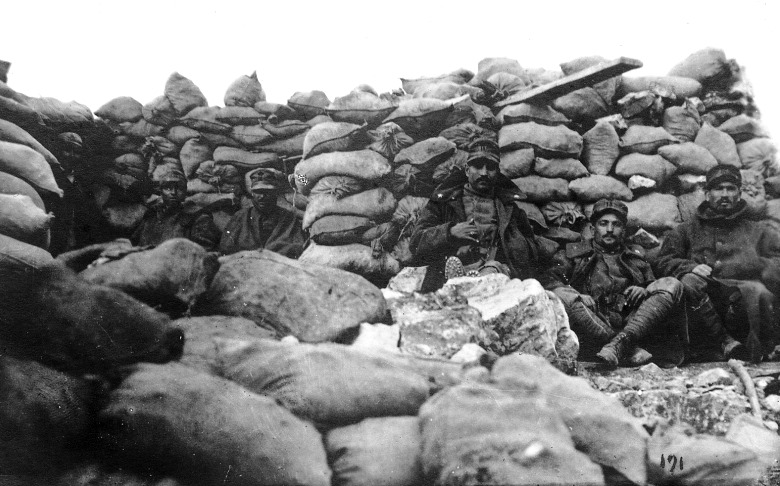

It assumed from the beginning great strategic importance in the Italian plans. Most of its military resources were poured out on its shores in an attempt to break through the Austro-Hungarian defences and open the way to the heart of Austria By the impact of the 2nd Army of General Pietro Frugoni and the 3rd Army of Duke Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy-Aosta. From the basin of Plezzo to Mount Sabotino, overlooking the low hills in front of Gorizia, the Isonzo flows through two steep mountain slopes, forming a barrier almost unalterable. The entrenched lines of the two armies had to adapt to the orography and characteristics of the battlefield.

The Austro-Hungarians abandoned the valley of Caporetto, faced the Italian wards on a nearly everywhere dominating line, which departed from Mount Rombon, passed through the Tolmin-bounded field, and then connected the steep right-hand side of the river to the left, in correspondence With the tombs of Mount Sabotino. From Sabotino the Austro-Hungarian trenches defended the town of Gorizia until the Isonzo, to graft on the four peaks of the massif of San Michele and finally went to the sea along the first cove of the Carso, passing through San Martino del Carso, Monti Sei Busi, Lake Doberdo, Debeli, and Cosich mountains.

THE FIRST OFFENSIVE STEP

At the start of the hostilities, Italian troops roared almost everywhere across the border to ensure good starting points for subsequent operations. On the front, Giulio conquered the basin of Caporetto, the ridge between Isonzo and Judrio, and raged in the Friuli plain occupying Cormons, Cervignano and Grado.

But progress became more and more complicated and bloody because the enemy, in addition to a long experience of trench warfare, also enjoyed the advantage of positions – all dominant.

At the beginning of June, Gradisca was occupied, and forced Isonzo to Plava, created a bridgehead that prevented the enemy from communicating to the valley bottom. Monfalcone then settled, and the 16th conquered Monte Nero.

THE FIRST FOUR BATTLES

Concluding the first offensive leap, the enemy was then engaged, along the Isonite front, in eleven offensive battles in which Italian troops profited largely from value and blood.

This was the case for the Jeonszo 29 months of bitter warfare that, if they were bloody for the Italian troops, also cost the enemy terrible tardiness that made it impossible to feel its weight on other fronts. In subsequent waves, the generous Italian youth faced the fire of machine gunners and enemy cannons, launched against the “terrible” network in which groups of men voted to sacrifice opened their gates with rudimentary and hazardous means. A year later, there was a new weapon – the bombard – to facilitate its task and reduce the loss of young human lives.

The goals of the first four battles, fought in 1915, were the two bridgeheads of Tolmin and Gorizia on the right of the Isonzo and the bastion of the Karst.

In spite of the impetus with which Italian troops fluttered against the well-organized enemy defences, losing the blossom of its fighters, the results were scarce. They, however, wandered, installing striking enemy forces and recalling others.

THE FIFTH BATTLE (March 1916) was intended to favour the French ally, preventing the enemy from transferring troops to the Verdun front, where the Germans had launched an extraordinary attack. The struggle was particularly harsh between S. Michele and S. Martino, but with very modest results.

At the dawn of June 29, 1916, in the area of St.

Michael, his tragic appearance appeared a new cruel means of struggle: asphyxiating gas. Surprised in sleep, in just a few minutes, 2,700 men in the XI Army Corps died, while another 4,000 were severely intoxicated. But, with a tremendous effort of the will of the survivors, the situation, initially compromised, was readily restored.

THE SIX BATTLE OF THE HONEY (4 – 17 August)

The plan included two significant attacks on the sides of the Gorizia camp, from the heights of Sabotino to Podgora and S. Michele to Doberdo; Other diversionary action had to be made with a reasonable advance on the Monfalcone sector.

The operation, entrusted to the 3rd Army, had been carefully prepared; For the first time on the Italian front, the cannon was attached to the bombard, born to break the barrier of the cross-links. After a warlike preparation, the critical positions of Sabotin and the so-contrasted peaks of St. Michael have gained momentum. On August 9, our avant-gardes entered Gorizia and then attended the Walloon.

The 6th Battle of the Isonzo was a great success for the Italians, who inflicted on the Austrians the loss of 41,835 men and massive war material.

In 1916 there were still three battles: the seventh the eighth and the ninth, with which despite the unchanged momentum and indomitable tenacity, modest results were achieved: the defence was even more vigorous than the attack.

The spring of 1917 was marked by the DECIMA BATTAGLIA

(May 12 – June 8), which was aimed at the conquest of the overhanging mountain bastion on the Isonzo between Plave and Gorizia and the critical mass of Hermada.

Violent fighting took place, especially on Vodice and Monte Santo, which was occupied and lost many times. However, they were occupied by the Monte Kuk, Jamiano and the 21st part of Monfalcone.

The Seventh Battleground (18 August – 12 September) was aimed at the Bainsizza plateau, which constituted the enemy a good starting point for its offensive and also represented the natural coverage of the Chiapovano Valley, used by the Austrians for the safe Displacement of men and means between the Karst and the Tolmino Basin.

The offensive also developed on the Karst, and this competed well with the sea monitors and boat batteries. At the expense of serious sacrifices, the Italian troops forced the Isonzo in more places and so progressed so rapidly on the western edge of the Bainsizza plateau to force the enemy to fall back on a more retarded line leaving the Italians Jenelik, the Kbilek, The Monte Santo, 20,000 prisoners, as well as large amounts of weapons.

The total losses in this great battle amounted to 143,000 Italians and 110,000 Austrians between dead, wounded and missing. After this battle, the Austro – Hungarian army was reduced to conditions that could not support another Italian attack.

In order to try to restore its destiny, the major German and Austro – Hungarian states decided to launch a great offensive against the northern wing of the 2nd Italian Armed Forces before the winter months, (DODISIVE BATTLE OF THE SISON).

At the dawn of October 24, the 14th Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces, formed by eight Austrian and seven Germanic divisions, vigorously attacked Plezzo and Tolmino, the Italian lines, previously disrupted by a massive projectile fire and gas fire, succeeded almost entirely Overtake them by quickly reaching the basin of Caporetto. Psychological factors, as well as the coincidence of unfavourable circumstances, contributed to transforming a tactical success of the enemy into a strategic victory. This led to the defeat of the Julius front and forced the Supreme Command to order the retreat on the first and on the Piave to prevent the encirclement Of the 3rd Armada. The balance and heroic The behaviour of the 3rd Armed Forces enabled the Army to save on the right of the Tagliamento and made possible the next resistance to the right on the right line of Piave on the Grappa and the Altipians, where they inflicted all the desperate enemy attacks. From those positions, at the end of October 1918, Italian infants jumped over to overwhelm the defeated enemy.